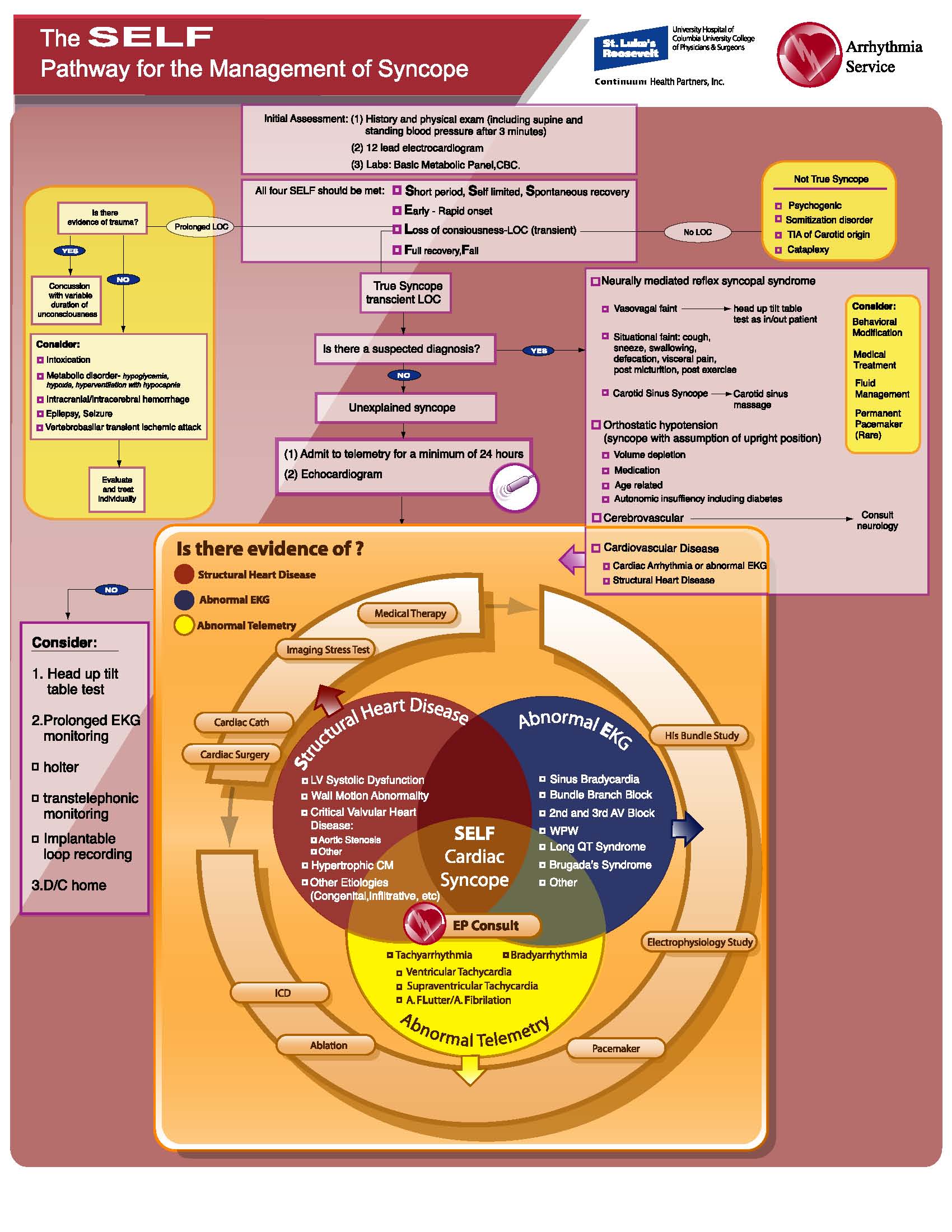

The SELF Pathway for the Management of Syncope

Syncope is a syndrome consisting of a relatively short period of temporary and self-limited loss of consciousness caused by transient diminution of blood flow to the brain (1, 2).

The term derives from the Greek word synkoptein, meaning “to cut short” (3), and is used to classify a common clinical problem. The incidence of self-reported syncope is 6.2 per 1000 person-years in the Framingham study with a cumulative incidence of approximately 3% to 6% over 10 years. In selected patient populations, the lifetime prevalence of syncope could reach almost 50%. In the United States, 1 to 2 million patients are evaluated for syncope annually, making up 3% to 5% of emergency department visits, and 1% to 6% of urgent hospital admissions (4).

Although several guidelines have been published for the diagnostic approach to patients with syncope, none has been validated prospectively and none applies to every clinical situation encountered (2, 5-6). Most guidelines do not specify the level of detail needed to create a structural evaluation tool for these patients. Therefore, these guidelines provide only a framework to approach the diagnostic evaluation of this difficult problem. Recently the American Heart Association in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology and the Heart Rhythm Society published a scientific statement on the evaluation of syncope(7). As with the prior guidelines, we found this statement to be very difficult to follow. To address this issue we developed a novel pathway which is comprehensive, yet simple, and provides guidelines for the management of all patients presenting to emergency departments with a complaint of syncope (Figure 1.) Our primary purpose in the evaluation of the patient with syncope is to determine whether the patient is at increased risk for death.

Goals of the Pathway

(1) Initial assessment of a patient with syncope

The approach to the patient with syncope begins with a meticulous medical history. In most patients the cause of syncope can be determined from the history and the physician examination alone. Orthostatic hypotension and autonomic dysfunction can be identified by measuring blood pressure and pulse rate in the upper and lower extremities in the supine and upright positions. A12 lead electrocardiogram and lab tests for a basic metabolic panel and complete blood count should be performed in all patients with syncope.

(2) Definition of true syncope

Syncope falls within a larger category of clinical conditions that cause loss of consciousness. Syncope comprises part of a subset in which the loss of consciousness is transient. We have created the acronym of SELF which reflects the four criteria that should be met in order for an event to be considered true syncope.

These criteria include:

S- Short period, self limited, spontaneous recovery

E- Early-rapid onset

L- Loss of consciousness- transient

F- Full recovery- fall

Patients who did not lose consciousness will be defined as “not true syncope”

Patients with prolonged loss of consciousness will be evaluated and treated individually as suggested.

(3) Classification of syncope when there is a certain or suspected diagnosis

Fig. 6 provides a pathophysiological classification of disorders causing true syncope with a transient loss of consciousness:

-Neurally mediated reflex syncope syndrome refers to a reflex that, when triggered, gives rise to vasodilatation and bradycardia.

- Orthostatic hypotension syncope is defined as syncope with assumption of upright position. Volume depletion is an important cause of orthostatic hypotension.

- Cardiovascular disease

Structural heart disease can cause syncope when circulatory demands outweigh the impaired ability of the heart to increase its output. Cardiac arrhythmia can cause a decrease is cardiac output, which usually occurs irrespective of circulatory demands.

(4) Initial management of patients with unexplained syncope

Our minimal requirements for the evaluation of unexplained syncope include transthoracic echocardiography and admission to a telemetry floor with a minimum of 24 hours of cardiac monitoring.

(5) Management of cardiac syncope

The major goal of the evaluation of syncope in patients with heart disease is to identify a potentially life threatening diagnosis. This necessitates an evaluation for structural heart disease, abnormal EKG and abnormal telemetry.

Structural heart disease includes critical valvular heart disease such as aortic sterosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, wall motion abnormality and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, suggestive of cardiomyopathy. Work up and management of these patients caninclude medical therapy, stress testing with cardiac imaging, cardiac catheterization and possible percutaneous coronary intervention or cardiac surgery. A definition of an abnormal EKG includes evidence of sinus bradycardia, bundle branch block, advanced 2nd or 3rd AV block Wolff-Parkinson White syndrome or the rare Long QT Syndrome and Brugada’s Syndrome. Work up of these patients may include a His bundle study or a complete electrophysiologic study.

Abnormal telemetry is divided into bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias.

The management of bradyarrhythmias may include an electrophysiologic study with or without subsequent pacemaker implantation. Trachyarrhythmia includes ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. The work up of these patients may include an electrophysiologic study radiofrequency ablation or a device therapy with pacemaker or implantable defibrillator..

We recommend that all patients with a diagnosis of cardiac syncope have an electrophysiology consult during their hospitalization.

(6) Management of patients with unexplained syncope but with no evidence of cardiac etiology

In the absence of underlying heart disease, syncope is not associated with excess mortality. Our recommendation for these patients is early discharge home, with consideration of head up tilt table testing and prolonged EKG monitoring (including Holter monitoring, trans-telephonic monitoring and implantable loop recording).

Conclusion

This comprehensive pathway provides a detailed algorithm for the management of syncope emphasizing the search to identify a potentially life threatening cardiac diagnosis. Our goal is to validate this pathway in large numbers of patients and to assess health care provider satisfaction and impact on efficiency.

REFERENCES

1. Bendit DG., MD, Van Dijk G J, MD, PhD, Sutton R, et. al. Syncope: Curr Probl Cardiol, April 2004; 152-229.

2. Brignole M. Alboni P, Benitt DG, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Bloch PE, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope. Eur Heart J 2001; 22:1256-1306.

3. Elpidoforos S. Soteriades, M.D., Jane C. Evans, D.Sc., Martin G. Larson, Sc.D., Mind Hui Chen, M.D., et al. Incidence and Prognosis of Syncope: N Engl J Med, September 19, 2002; Vol. 347, No. 12; 878-933.

4. Win K. Shen, MD; Wyatt W. Decker, MD; Peter A. Smars, MD; Deepi G. Goyal, MD; et al. Syncope Evaluation in the Emergency Department Study (SEEDS). A Multidisciplinary Approach to Syncope Management: Circulation 2004; 110:3636-3645.

5. Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, et al. Diagnosing syncope: part 1: value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. The clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126:989-996.

6. Linzer M, Pontinen M, Gold DT, et al. Impairment of physical and psychosocial function in recurrent syncope. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991; 44:1037-1043.

7. Strickberger SA, Woodrow Benson D, Biaggioni, et al.AHA/ACCF Scientific Statement on the Evaluation of Syncope: From the American heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: In Collaboration With the Heart Rhythm Society: Endorsed by the American Autonomic Society. Circulation 2006; 113:316-327.